It’s getting harder to make this list each year, because I’ve already covered a lot of my favorites in 2018, 2019, and 2020. I’m trying to think outside-the-box for new gift ideas, which means there’s a good chance the beekeeper you’re buying for doesn’t already have these items. But be sure to check out those previous posts for more ideas.

Before jumping in, know that I am not affiliated with any of these companies or products. I include links so it’s easy for you to find and buy them if you choose, but I don’t make a penny from any purchases. Each item here is included because I like it, not because I’m shilling products.

Top Pick, Under $10

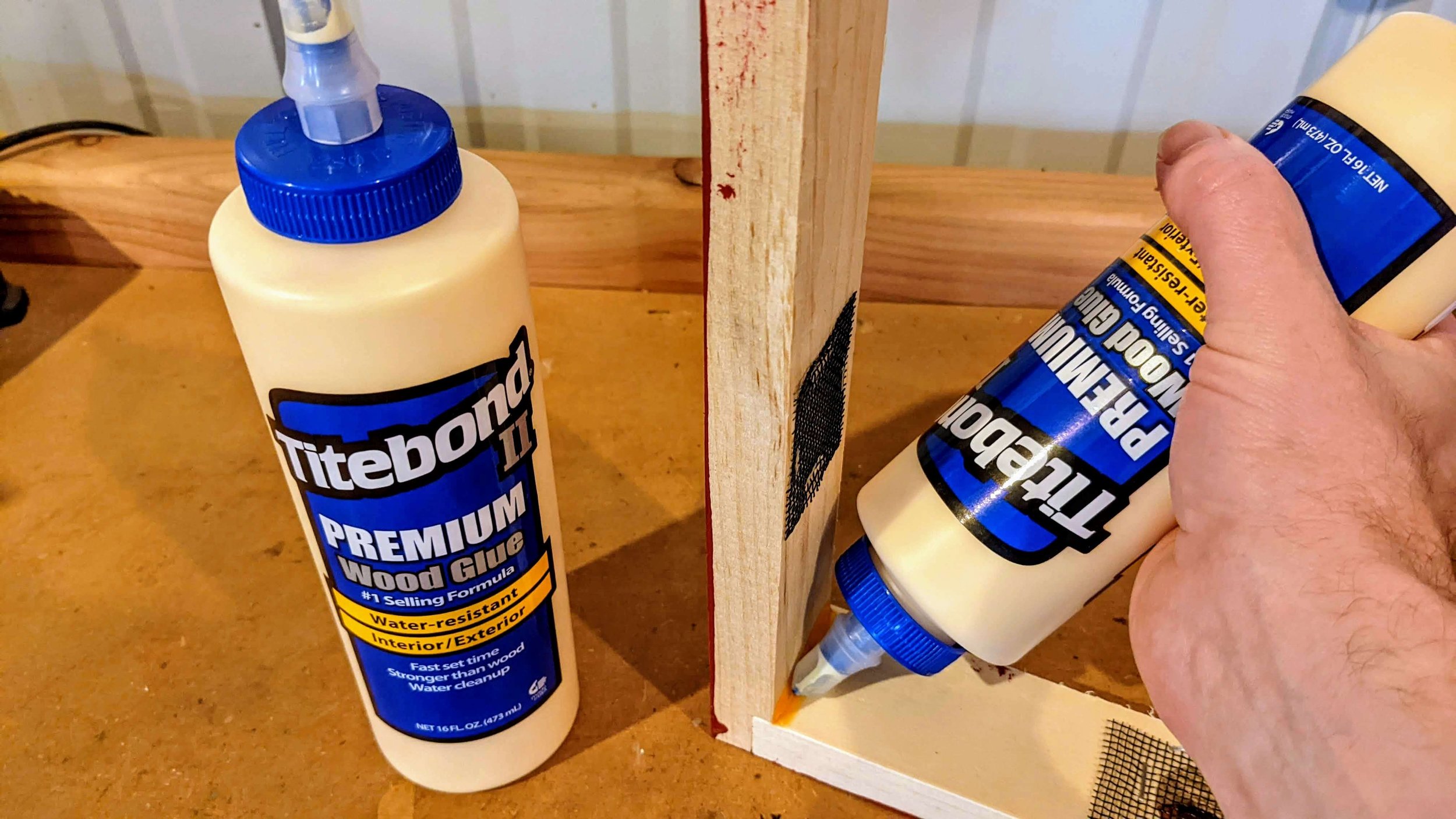

Wood glue is great for hive assembly and also for reducing small hive beetle infestations

Wood Glue

Wood glue is an unsung hero of beekeeping. We use copious amounts of the stuff when we’re assembling hive components, which helps keep boxes and frames strong enough to handle the abuse we inflict on them. A lesser known, but as important, use for wood glue is sealing any gaps and crevices in hive equipment. By filling these cracks, we limit hiding spots and egg nurseries for the dreaded small hive beetle. I apply wood glue to every piece of woodenware prior to using it, which has almost eradicated small hive beetles in my hives. You can pick up high-quality Titebond wood glue at any local hardware store for under $10.

Top Pick, $10-$20

This American-made garden trowel has stood up to serious abuse on our rocky property

Garden Trowel

Sooner or later, most beekeepers turn into gardeners. That’s because it becomes super obvious how connected honey bees are to the plants around them. When I started getting into native plantings for my bees, one of the tools that kept failing was the humble garden trowel. The problem is the handles on cheap trowels at big box stores eventually separate themselves from the scooper. So I found this trowel by Wilcox. It’s made in Iowa, and can be had for as little as $18.99 on Amazon. This trowel has been indestructible for us, even with all the abuse from our rocky clay soil. And it’s an important tool in our quest to grow as many pollinator-friendly plants as possible.

Top Picks, $20-$50

A “flower pot” swarm trap mounted in a tree near my bee yard

Swarm Trap

Every beekeeper should have at least one or two swarm traps. As soon as we see signs our bees are preparing to swarm (which they try to do just about every spring), we almost have a civic duty to put out traps in order to minimize the risk of our bees swarming into the neighbors’ houses. Besides that responsibility, beekeepers can reduce costs by capturing bees instead of buying bees. My favorite type of swarm trap is the “flower pot,” which is basically waxed paper machete in the shape of a pot. These are really cheap, reusable, and lightweight. The weight is my favorite thing about them, because lugging a heavy wooden swarm trap up a tree is no fun. And it’s even less fun lugging it back down with a swarm of bees inside. Mann Lake sells these swarm traps for $31.95 each, and for my money they’re a must-have.

This old Brushy Mountain frame jig is like having an extra set of hands for assembling bee frames

Frame Jig

Every beekeeper should assemble their own frames at once in a while. I don’t have a problem with buying frames pre-assembled, but every now and then I need frames fast, and the only ones available at my local bee store are unassembled. Assembling these frames can be tedious, messy, and time-consuming. You end up trying to hold every piece of wood in position while driving a nail through them with your glue-covered hands. But a frame jig makes the process a thousand times better, to the point that I actually find it meditative. A honey bee frame is made up of at least four wooden pieces that have to be nailed and glued together, all while keeping them at right angles. A frame jig holds these pieces in place so you can do 10 frames at a time, much quicker and at a higher quality (i.e. not crooked) than doing it freehand. My frame jig came from Brushy Mountain, which isn’t in business anymore. But it looks like at least one company (Texas Bee Supply) is making a similar design, and offering it for a surprisingly low price of $35.59 plus shipping.

Top Pick, $50-$100

I write “Honey” on my food-grade buckets so I know these are only to be used for storing honey

Honey Buckets

“You got me buckets for Christmas?” is a question none of us wants to hear. But the truth is beekeepers need buckets. And not just any buckets. They need clean, food-grade buckets for extracting and storing honey. They also need them for mixing syrup to feed their bees, assuming they’ve got more than a few hives. Buckets around me tend to get repurposed for any number of property and home maintenance uses—some of which involve chemicals that make them off-limits for beekeeping. So I’ve got a good set of BPA-free food-grade buckets I set aside for beekeeping use only. These run $69.99 on Amazon for a set of six, which is enough for most hobby beekeepers. If you want to make them more of a unique gift, customize them by painting or stenciling some honey bees on them, or even the beekeeper’s business name. That’ll help keep the buckets from being used to wash their car, and honestly would make a great, thoughtful gift.